This text originally appears in my publication On Burnout: A Transdisciplinary Artistic Research Project – Research Methods and Devices. This version expands upon the original and has elements rewritten to be more ‘blog friendly.’ If it feels like a mix of tones – from more formal to more personal – this is why.

Asemic writing, as both a practice of experimental writing and as a visual arts practice around signifier and signified, has been useful and instrumental in my long-term artistic research project on burnout.

I gravitated towards asemic writing and began exploring and expanding it in practice with others because of how it engages the body differently when approaching writing about lived experiences than more conventional ‘creative writing’ exercises. It stems and converges with the aspect of this project that recognises the body as a producer of knowledge. More on that here with this intervention in the form of a fictional, the Society of the Absent Present.

Asemic Writing

Asemic writing has been a useful tool and practice in expression of the body and mind in complimentary ways. Asemic writing it commonly defined as writing with no semantic content. Meaning, the content of the visual markings of the writing are semantically open for the viewer’s interpretation.

By asemic artist Mirtha Dermisache

During my research project two approaches of asemic writing collided. I first arrived to an asemic experiment after countless conversations and interviews discussing burnout, listening to how common it was in these accounts for people to explain how words escaped them when it came to describing how their body felt, and how they felt in their body. Especially in the situation of a whirring mind with a lot of heavy and consuming thoughts that contrast with a fatigued—also heavy—body full of various sensations. A frequent remark was about learning to ‘listen to one’s body’ or that their body had been ‘speaking’ to them for a long time in ways that were later realised to have been ignored.

When the body speaks, what language does it use? If our usual words escape us, could it be that the body is transmitting a knowledge in a language of its own?

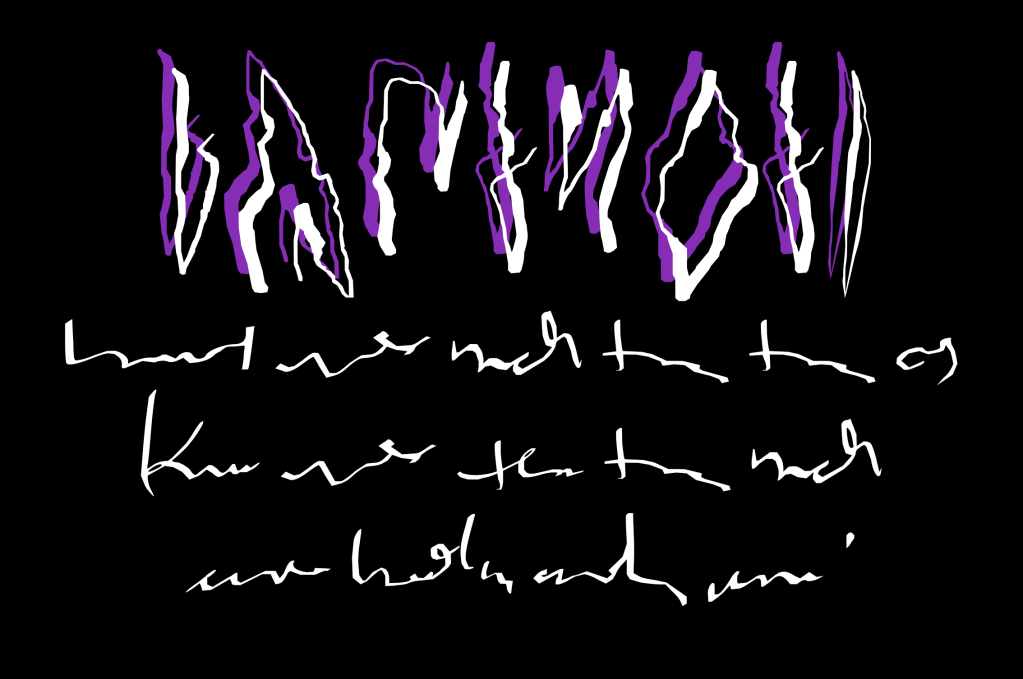

This was my starting point for a project during the summer of 2021 to develop an asemic typeface to represent the body speaking via the Faire Parler les Lettres (Let Letters Speak) summer school at le Signe in Chaumont, France, held by type designer Naïma Ben Ayed as part of the Biennale Internationale de Design Graphique ’21 (International Graphic Design Biennial ‘21). Ben Ayed, who is specialised in Arabic type design, created the programme to deliberately give precedent to non-Latin based writing systems, specifically calling for participants who wanted to learn how to make digital typefaces and were interested in experimenting with the notions and intersections of language and letterforms.

In my application I explained my desire to create a digital typeface that was asemic, one that took inspiration from the non-verbal language of the body—the ‘language’ that doesn’t seem to compute with one’s usual words, can be international and universal (we may not speak the same verbal language, but it is possible you can relate to how my body feels after exertion, how my period pains effect my digestion, what it is like when a headache is reverberating from between the eyebrows)—and simultaneously could create a vacuum of meaning that lies open for the reader to fill in and interpret.

‘Asemic art, after all, represents a kind of language that’s universal and lodged deep within our unconscious minds. Regardless of language identity, each human’s initial attempts to create written language

– Satu Kaikkonen, contemporary Finnish asemic artist/writer

look very similar and, often, quite asemic.

In this way, asemic art can serve as a sort of common language—albeit an abstract, post-literate one—that we can use to understand one another regardless of background or nationality.’[1]

We began with hand sketching. My drawings and bodily expressions turned into digital forms that I learnt how to prepare and morph and eventually assign to keys using Glyphs 3. The result is SOMASOMA, a digital asemic typeface inspired by the body as a producer of knowledge with its own language it sings in. Posters of SOMASOMA were included in the biennale’s showing and published in a collective riso-zine with all the resultant designs from the summer school.

The statement (as pictured above) reads:

SOMASOMA is an asemic typeface – meaning that is has no specific semantic content. Rather, the font proposes what happens when the body speaks and words escape it, try as one might to scrawl out the experiences of pain, suffering, or even euphoria.

Inspired by the experience of severe burnout, SOMASOMA attempts to fill the space that semantics struggle with when it comes to communicating how the body feels, what our bodies know, and what happens when we try to describe what is going on for us (psycho)somatically. Instead, SOMASOMA offers a vacuum of meaning to be filled by both the writer and reader as they feel, decide, and desire.

ALREADY A NATURAL ASEMIC?

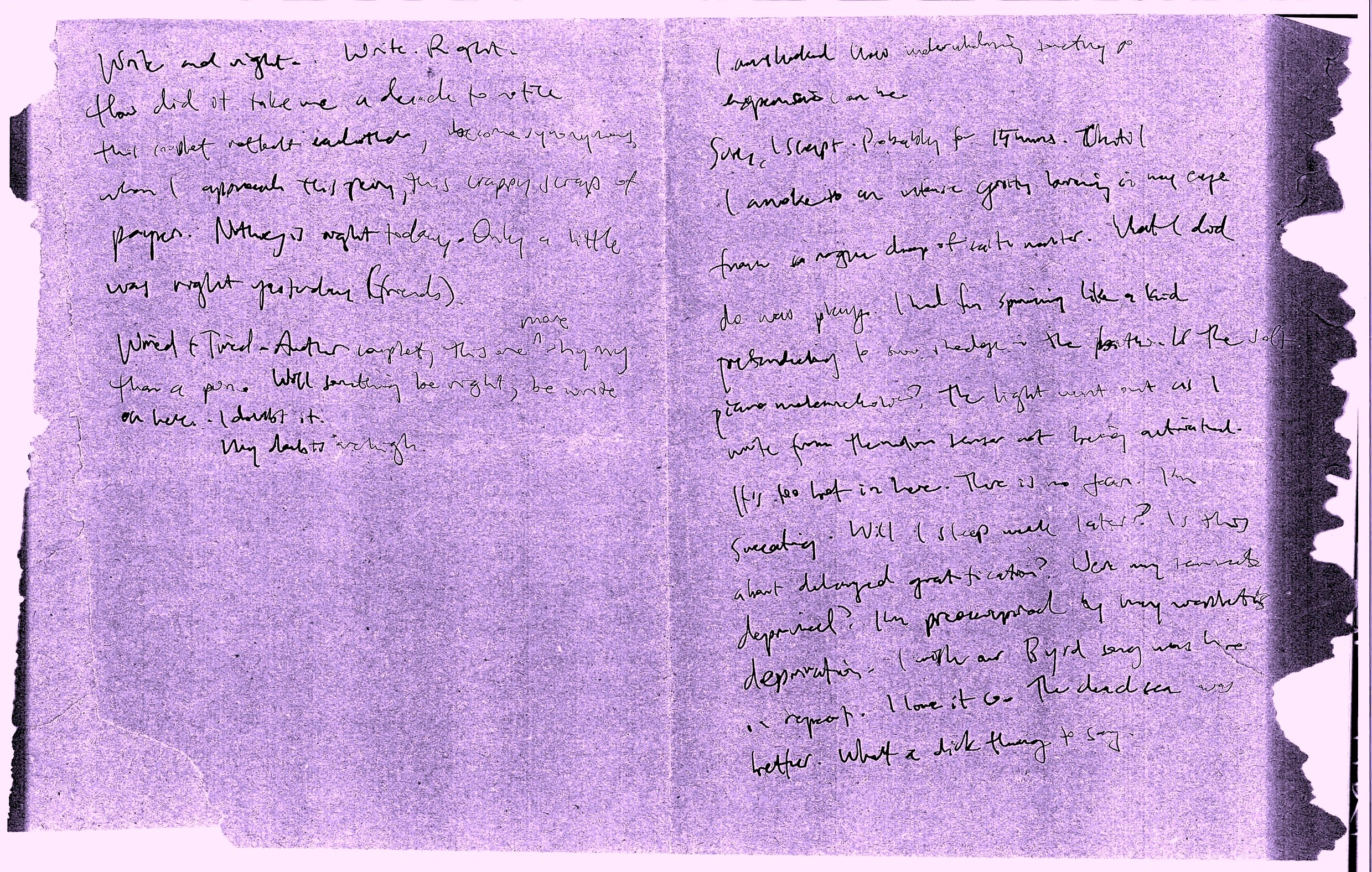

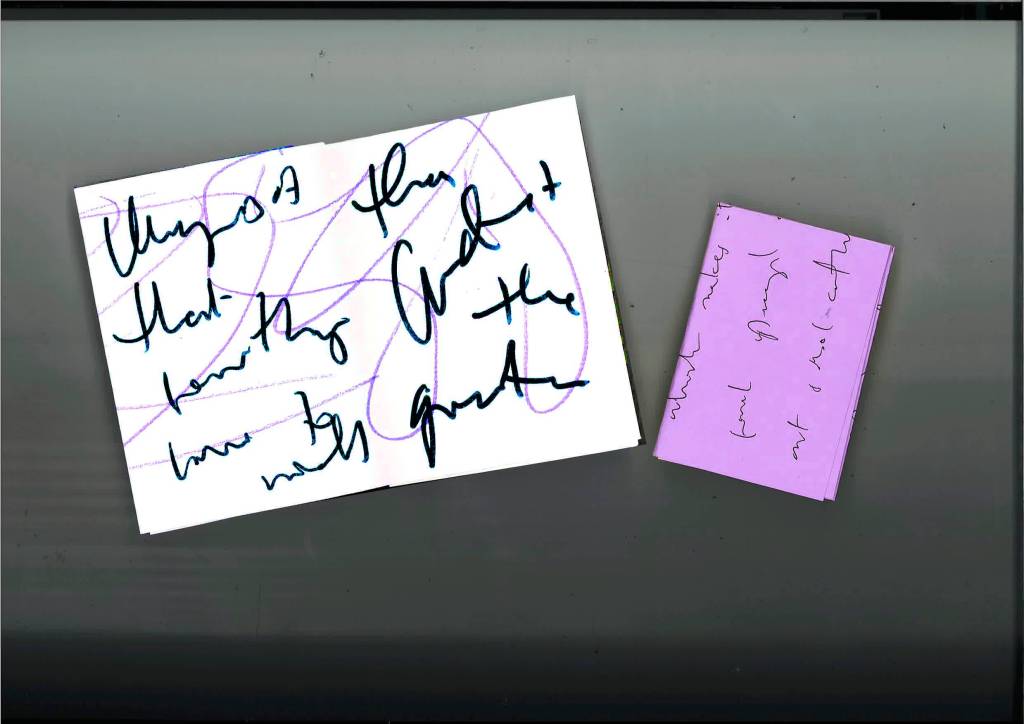

By the time I got to Le Signe, I knew I had developed an inadvertent asemic writing practice because when I write fast and free my handwriting becomes illegible. Definitely to others and often to myself. From here I conceived of a series of ‘warm up’ exercises for Delphine Chapuis Schmitz’ experimental writing labs, as part of the master Transdisciplinary Studies programme at Zurich University of the Arts, that were based upon ‘automatic writing’ or stream of consciousness writing where legibility of the text was unimportant.

In Julia Cameron’s infamous The Artist’s Way (1992) the foundational practice that is to be exercised every day throughout the prescribed syllabus Cameron offers to those keen to ‘recover their artistic selves,’ is the morning pages. With the morning pages, one sits down first thing in the morning (every morning) and writes three pages, non-stop, of whatever comes to mind. This is intended to be a kind of ‘mental dump’ where the content doesn’t matter and they need never to be read again. When I write morning pages they reliably become sheets of scrawl, partially due to speed since I want to get them over and done with, or sometimes there is so much to get out the writing becomes frantic, and partially because my handwriting is naturally quite doctor-esque. The physical action of doing such writing feels liberating, as does the knowledge that these words and their content never need to be read again. It is fun and therapeutic to write writing that has no need to be read.

– Jess Henderson

Introducing the morning pages and the concept of writing writing that’s main purpose is not about transmitting meaning to the experimental writing class was thrilling to observe. The participants who also came from the Transdisciplinary Studies programme jumped right in and, I guess, were already accustomed to ‘crazy’ practices that could be perceived as having no purpose. Those who came from other programmes though, for example art education, curatorial studies, journalism or cultural publishing, had differing responses. The way it took a minute for them to get their head around what was being asked of them, the questions about coming to a writing class to write the illegible, indicated to me an extent of asemic writing’s potential and conceptual richness.

UNCOVERING A LOOPHOLE

In my research on asemic writing, its practices and practitioners, its oscillation between visual art and writing and semantics (or lack thereof,) I perceive a sort of loophole for when handwriting enters this realm. It reflects writing though slides out of being part of a completely existing writing system. If presented to viewers other than the creator, the viewer is encouraged into a state hovering between reading and looking. Perhaps without any verbal sense, it retains a textual sense. Maybe understanding—if there is an understanding to be had—could come from an aesthetic intuition? In theories surrounding asemic writing, an idiom exists that ‘True asemic writing occurs when the creator of the asemic piece cannot read their own asemic writing.’ However, I see an overlooked or unnoticed field of asemic writing emerge when one’s handwriting becomes illegible to others. This practice makes for work that is without semantic content to a viewer, but can have semantic content for the maker—even if it is illegible. It is possible to write writing you cannot read, can somewhat read, or just know what it says.

This opening loops back to the therapeutic quality of the physicality of such handwriting, bringing in another therapeutic effect of spilling yourself on the page whilst saying things that nobody knows are there, but you. A type of ‘healthy secrets,’ the pleasure of writing in a personal code. A childlike return to when one didn’t know how to read or write, but had seen writing done and wanted to replicate what adults could do. Pre-literate children are natural asemics. Writing with such intent to present to their adults what appears to be a page of scribbles, though they can explain exactly what it says.

A type of ‘healthy secrets,’ the pleasure of writing in a personal code. A childlike return to when one didn’t know how to read or write, but had seen writing done and wanted to replicate what adults could do. Pre-literate children are natural asemics.

–From On Burnout by Jess Henderson

SHARING THE PRACTICE

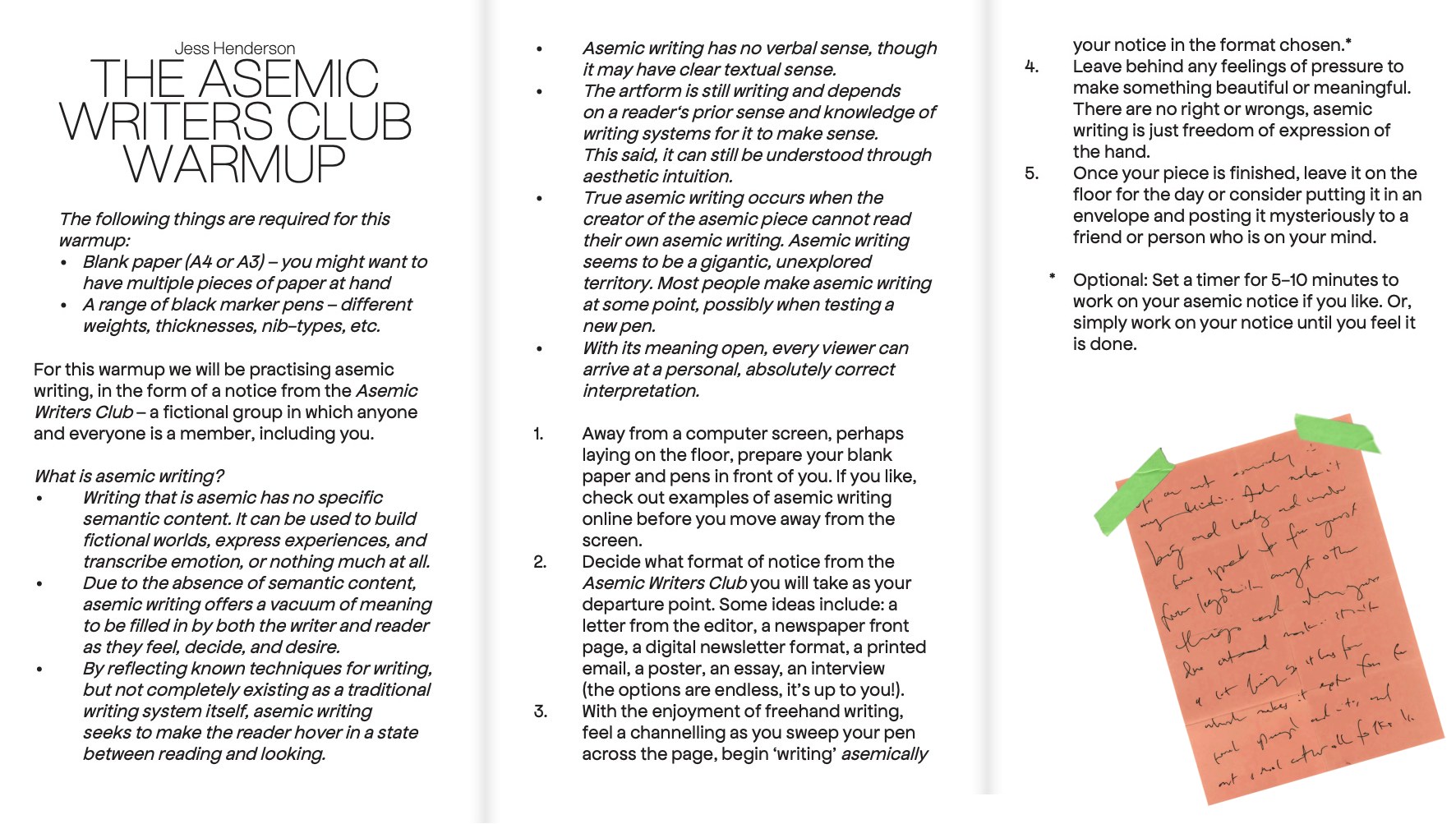

With asemic writing firmly in my own artistic practices, and useful as an artistic research device in discussion groups, when I was asked to contribute to a book of warm-up and cool-down exercises in relation to art making or group workshops, I created the ‘Asemic Writers Club’ warm-up, which can be read below.

Feel free to click and save to try it out.

It is included in a book called Warm-Ups and Cool-Downs put together by Eirini Sourgiadaki, with four more of my contributions alongside many other great ideas from a wide range of excellent contributors. Published by HumDrum Press, you can download the whole ebook for free here.

“The concept of warmups and cooldowns is the simple and essential engagement of the bodymind in the process of nurturing motivation and drive.

[…] All of the warmups and cooldowns ideas collected in the pamphlet have an artistic character, are non-exclusive, and are open to a wide audience-base to use individually or within a group, in order or randomly selected, with or without instructions.”

From Warm-Ups and Cool-Downs, the book

FOLLOWING THE PRACTICE

I intend to keep posting about asemic writing, new work from my artistic practice, as well as exercises and ideas for experimentation with asemic expressions yourself. These will be sent out via my newsletter, which you can subscribe to here.

[1] Schwenger, Peter. Asemic: The Art of Writing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.